Emergency medical services for victims of rape—defining the role of clinical sexologists in providing clinical assessment and collecting forensic evidence

Sexual trauma is defined as exposure to a life event(s) whereby someone’s personal space and health were evaded for sexual gain. Common examples of sexual trauma include non-penetrative assault and rape. There is also a possibility of experiencing long-term psychological trauma caused by being exposed to sexual assault, verbal threats, stalking—any behavior that threatens the person’s sexual self (1). We know from the literature that many survivors of rape do not seek post-assault care (2), which is vital for two reasons. First, the patient can receive a specialized evaluation for possible trauma and get everything documented at the same time, should they seek legal help; Second, the female survivors might request emergency contraception, should there be a chance of becoming pregnant as a result of the assault. Another problem is that many emergencies department staff lack training in helping this uniquely vulnerable group of patients. Research has shown that most physicians have not been trained in identifying possible victims of human sex trafficking (3) or feel uncomfortable seeing adolescents who endured sexual assault (4). Therefore, it is important to consider possible solutions to these existing issues. Indeed, some have attempted to figure out whether training nurses in treating survivors of sexual assault is effective (5). We still need better solutions for helping the patient by, for instance, employing a specialized group of providers who have an interest in sex medicine—sexologists.

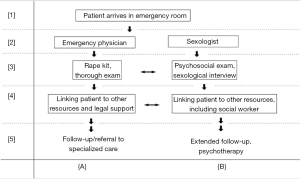

In this representative model, outlined in Figure 1, we describe how to provide optimal care to suspected victims of rape in an emergency services clinic. Throughout our discussion of this model, the central assumption is that both the physicians and clinical sexologists can work together to adequately care for these patients, each having distinct provider role. Emergency physicians’ main duty is the physical evaluation, treatment of traumatic injuries, and collecting forensic evidence upon receiving patient’s consent. Clinical sexologists supplement medical care by performing a full sexological interview, including an evaluation of social history, prior experience of psychological trauma, and sexual practices. This model assumes that there are at least two points of care, denoted on Figure 1 as cross-section points 3 and 4, where both physician and sexologists have an opportunity to connect the patient to outside support and resources. Depending on the unique set up of a given emergency room department, the help of a sexologist may not be required for every patient—if they didn’t experience extensive physical and psychological trauma. The state of health and mind of each patient needs to be thoroughly considered by an attending physician. If he or she decides that the help needed goes beyond their time availability and clinical scope, then they should make every effort to involve a clinical sexologist in follow-up care.

One area where an emergency physician might be ineffective in providing care is offering extended, compassionate psychotherapy. This is a forte of clinical sexologists, trained in conducting psychosocial evaluations and psychological counseling. The emergency department is not conducive to doing such work. Therefore, it is advisable to have on the team a dedicated sexologist, who can provide supplemental care.

The patient arriving in the emergency room (point 1, Figure 1) with signs of sexual trauma would be given the opportunity to see a clinical sexologist immediately after an initial consultation with their physician. The physician should evaluate whether the patient’s condition is stable (= the patient’s psychological state, that allows her or him to participate in treatment and being open to therapeutical conversation with the physician and clinical sexologist), whether there is any trauma that needs to be documented by the doctor, and to provide treatment and medications that improve the initial state of distress and pain. If the patient implies or admits to, being a victim of sexual assault, it is appropriate for the physician to provide initial consultation and seek permission to collect and document forensic evidence. Subsequently, the patient should be informed about the opportunity to speak to a clinical sexologist as part of the comprehensive evaluation plan (point 3, Figure 1). This way the patient is reassured about receiving appropriate medical care, and gets connected to a clinician who can more appropriately manage psychological trauma; concurrently, the sexologist may have the opportunity to understand the socio-cultural situation of the patient better, provide counseling regarding possibly negative consequences of sexual assault [i.e., pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs)], and offer to document everything in greater detail.

In the traditional emergency room setting, it might be difficult to expand expert care for victims of rape. Physicians and sexologists (point 4, Figure 1) have a unique opportunity to serve as information points. Physicians can aid in collecting evidence required by law that the patient can then use to establish a defense line against their perpetrator. The sexologist has a unique opportunity to establish care from the point of the traumatic event, create follow-up appointments to evaluate patient recovery and be there for the patient to provide specialized counseling outside of clinical setting. The sexologist may also know social workers competent in helping victims of rape; this allows them to work together to help the patient achieve optimal recovery.

The last step (point 5, Figure 1) tries to establish long-term support for the patient. The physician has a unique role in providing referrals to specialized care and drafting and signing any legal paperwork, detailing the traumatic ordeal of the patient. The sexologist should engage the patient in an extended therapeutic relationship. Alternatively, they may offer to act as chaperones of support, providing information about support groups, or dedicated professionals, for victims of rape.

In conclusion, this paper describes a new model for treating the victims of rape in an emergency room setting. The central assumption of this model is that there is a team of two dedicated providers—an emergency room physician and a clinical sexologist. The physician takes care of the medical treatment, collection of forensic evidence, and providing a referral to specialized medical care. The sexologist becomes the most crucial follow-up resource for the patient, providing compassionate and dedicated psychosexual therapy, as well as links the patient to other resources like local support groups and social workers who can provide additional services. The reason for proposing this model of care is that in its current state, most emergency rooms are not ideal places for providing specialized care to the victims of rape, especially when it comes to coordinating following up with the patient to see how they’re recovering.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ms. Agatha Markiewicz for tirelessly supporting the lab’s research.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Mhlongo MD, Tomita A, Thela L, et al. Sexual trauma and post-traumatic stress among African female refugees and migrants in South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatr 2018.24. [PubMed]

- Munro ML, Martyn KK, Campbell R, et al. Important but Incomplete: Plan B as an Avenue for Post-Assault Care. Sex Res Social Policy 2015;12:335-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibbons P, Stoklosa H. Identification and Treatment of Human Trafficking Victims in the Emergency Department: A Case Report. J Emerg Med 2016;50:715-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schilling S, Samuels-Kalow M, Gerber JS, et al. Testing and Treatment After Adolescent Sexual Assault in Pediatric Emergency Departments. Pediatrics 2015;136:e1495-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nielson MH, Strong L, Stewart JG. Does Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Training Affect Attitudes of Emergency Department Nurses Toward Sexual Assault Survivors? J Forensic Nurs 2015;11:137-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Sendler DJ. Emergency medical services for victims of rape—defining the role of clinical sexologists in providing clinical assessment and collecting forensic evidence. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2018;2:69.