An observational study of the effects of a clinical nurse specialist quality improvement project for clinical reminders for sepsis on patient outcomes and nurse actions

Introduction

Driven by the release of the fourth edition of the “Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC): International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016” institutional efforts continued to focus on improving routine patient screening for sepsis and improving adherence to bundled care for sepsis. Concurrently, the institution was planning for the transition to a new electronic health record (EHR). The EHR’s new documentation platform touted key features thought to be the answer to improving screening and treatment through clinical reminders (CRs) and automated sepsis screening.

Transitioning to the new product was not an easy feat and included months of design/build preparation followed by healthcare team education with practice sessions. After going live, members of the healthcare team found it hard to break old habits with documentation and to embrace new technology such as CRs/best practice alerts (BPAs). Frustration mounted with the amount of CRs disrupting flow of documentation for those involved in direct patient care, as well as those members not involved in direct patient care.

Background/literature review

Sepsis is life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by dysregulated host response to infection (1). Unrecognized, the body exhausts it defenses and progresses to a state of septic shock, a subset of sepsis with circulatory and cellular/metabolic dysfunction associated with higher risk of mortality; without treatment, death is imminent (1).

Evidence-based medicine is the integration of individual clinical expertise with evidence from scientific research (2). Bringing new evidence to the bedside in a timely manner to benefit the patient continues to challenge researchers, clinicians, and nurses alike. The SSC has been instrumental in its work, including publication of evidence-based guidelines to improve patient outcomes with sepsis. The guidelines incorporate the SSC Bundle which has been refined over the years incorporating new research. Odds ratio for hospital sepsis mortality decreases with every quarter of participation in the SSC initiatives (3).

A clinical decision support system (CDSS) is a means to support nurses and clinicians in provision of the latest evidence-based interventions, such as the SSC Guidelines. The Veterans Hospitals Administration first introduced the computer generated CDSSs in the primary care setting and CDSSs have since been transferred to many patient care settings. Effective clinical decision support (CDS) is intended to improve performance by giving the right information to the right person at the right time and place, making the correct action the easiest one to take (4). CRs can improve rates of delivery of screening and prevention services, and of services recommended by evidence-based practice guidelines and have evolved from paper algorithm/checklist to more sophisticated computer generated CRs. Meaningful use of the CDSS reminder by the healthcare team to ensure the suggested intervention gets to the patient in a timely manner, continues to challenge hospital administrators and quality officers. Current studies explore perceptions of CDSSs on technical issues and usability, overlooking social, cultural, administrative or organizational factors that may influence CDSS adoption (5).

The Institute of Medicine’s Quality Chasm series, clinical performance measurement and public reporting has led to initiation of carepaths and more recently CRs. Incentivized through healthcare reform, hospitals’ use of the EHR allows for automating documentation of patient care (6). This automation has the potential to add value of medical device data elements and evidence-based research (physiologic data, BPAs and alarm information) to provide clinical insight and support essential to patient care and safety (7). It is the combination of physiologic data (specifically temperature, heart rate, respirations) and laboratory values (white blood cell count) which triggers CRs for sepsis.

CRs are in essence an early warning system to alert care providers to a change in patient condition and provide prompts for provision of evidence-based intervention (8). The CRs are designed to: (I) reduce the likelihood that an aspect of care will be missed; (II) ensure care is well documented; and (III) increase standardization across patient care (9). CRs within the institution’s new EHR are called best practice advisories, a central tool in the CDSS delivering reminders or warnings to clinicians during their workflows. Advisories can appear based on specific patient, provider, and facility defined criteria.

Regardless of the intent for use, these CRs can become a nuisance to members of the patient care team. Frequent CRs can result in CR fatigue (decrease in response rates to reminders with increasing numbers of reminders and the decline in response rates over time) and potentiate nurse and clinician inattention to potential early signs of patient deterioration (10). Ignoring CRs and/or quickly dismissing them without use of critical thinking or delaying action (snooze), has the potential to cause failure to rescue situations; including omission of care, failure to recognize changes in patient condition, failure to communicate changes, and failures in clinical decision making (11). Contributing factors to reminder fatigue are many and may be deficiencies in computer algorithms, lack of knowledge of the pathophysiology and progression of sepsis, workload and patient demands.

After careful investigation of events resulting in patient death, permanent harm or severe temporary harm (sentinel events), The Joint Commission (TJC) publishes Sentinel Event Alerts (SEA) as a means for hospitals to improve safety and learn from the event. The Joint Commission’s “Sentinel Event Alert #54, Safe Use of Health Information Technology” builds upon a previous SEA, and calls on safely implementing health information and converging technologies centering on safety culture, process improvement and leadership (12). Factors topping the list of potentially causing health information technology sentinel events included, human-computer interface (33 percent)—ergonomics and usability issues resulting in data-related errors workflow and communication (24 percent)—issues relating to health IT support of communication and teamwork, and clinical content (23 percent)—design or data issues relating to clinical content or decision support (12).

Objectives

Much like research of clinical alarms, inappropriate or delayed response to CRs can lead to delay in care and dissatisfaction. Struggle with compliance with Sepsis National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measure (SEP-1) requirements, the new EHR was thought to be an answer for this problem but only served to complicate the issue with frequent CRs. Specifically, this project addresses the institution’s caring values (putting the patient first and no excuses). The innovation of the EHR’s electronic CR will be an asset for our project and specifically patient outcomes once adjusted. The project goal was to decrease alarm fatigue with CRs and improve appropriate timely nursing response to CRs.

Specific aims

(I) Reduce the number of CRs for sepsis in the inpatient adult population (>18 years) through CR customization; (II) improve patient safety through implementation of meaningful CRs and in turn decrease CR fatigue in nurses; (III) determine if nurses’ action to CRs for sepsis was appropriate and if it affected patient outcome (failure to rescue or delay in implementation of the sepsis bundle).

Hypotheses

A revision for the CRs for sepsis will: (I) decrease the frequency of nuisance CRs; (II) decrease nurse “alarm fatigue” thereby positively changing nurse action to CRs; (III) positively affect patient outcome by decreasing failure to rescue and/or time to sepsis bundle implementation.

Methods

Study design

The STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this observational study. The quality improvement project utilized a cohort study design in evaluating the effect of the redesign and education of the algorithm for sepsis CRs on nurse action (screening for sepsis). The primary endpoint for the project was a comparison of the number of CRs and compliance with sepsis bundle sepsis-related mortality before and after the implementation of the sepsis improvement program. The sepsis improvement program consisted of a combination of sepsis education, process improvement through change management, and a revision of the sepsis algorithm within the electronic CDS system.

The project team also utilized a cross-sectional study design to evaluate nurses’ current documentation practices (shift assessment and vital sign documentation) which may affect timing of triggering of CRs, to measure to what extent the nurses felt there were policies for sepsis in place (including adherence to policies) and to measure to what extent nurses felt they (and their patients) were affected by CR fatigue.

Setting

The quality improvement project site is a short-term acute care regional referral hospital accredited from TJC with level one trauma care designation known for clinical excellence. According to the American Hospital Directory, the hospital has 493 staffed beds with 18,986 documented discharges (13). The training and implementation phase of the project spanned July–August 2017 with go-live August 2017 with pre- and post-data extraction July 2017, January 2018 and July 2018 CRs.

Ethics approval

The project underwent an internal review process and received final administrative approval by The Office of Research Administration at the project site. The study was deemed exempt, as part of a hospital quality improvement initiative. All potentially sensitive audit data was accessible only to authorized personnel and stored using institutionally recommended security protocols.

Participants

Patient records with diagnosis related group codes for sepsis/septic shock were audited (July 2017, January 2018 and July 2018). Randomized sampling was determined with collaboration from the institution’s director of quality and SEP-1 requirements.

A convenience sample of acute and critical care nurses attending the biannual clinical education update in fall of 2017 (N=488) were eligible to participate. Survey participation rate was 42% (N=205). Nurses attending the education update, may not have completed the survey based on the department the nurses were employed (i.e., palliative care, adult or geriatric psychiatry, pediatrics, obstetrics, ambulatory surgery, etc.) and their feeling the information did not pertain to their specialty. Post-nursing survey included demographic information (Table 1). The survey pre-amble included notice of participation being voluntary with clear expectations of the project intent and assurance of confidentiality and data security. The survey tool was created by the principal investigator a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and reviewed by content experts, including the director of quality excellence, the director of nursing, and a nursing educator (certified in critical-care nursing). The sepsis CRs and nurse action survey focuses on current documentation practice (assessment and vital signs) and nurse intervention as it relates to triggering CRs (potential delay of trigger for sepsis CRs with delay in documentation), nurse response to CRs (action or inaction), and nurse perception of (“alarm fatigue”) CR fatigue. The survey was anonymous and did not collect any protected health information or any personally identifiable information (Supplementary file 1).

Full table

Interprofessional team

The stakeholders (project team members) were identified and included: emergency room staff (physicians, residents, and nurse manager), quality team, critical care and acute care nurse managers; CNS (original member of the organizational sepsis team), nursing informatics, nursing education, nursing administration, information systems representative, and new EHR platform documentation expert representative. Stakeholders who are involved in the process are more likely to actively use and disseminate the information they helped produce; and involvement from the beginning improves results, and helps ensure the process is relevant to users’ and had real-world applicability (14). The stakeholders joined the efforts of the organizational sepsis team (inception 6+ years prior) to delve deeper into the response by the healthcare team [nursing assistants (NAs), nurses, clinicians, and physicians] to identify the gaps. and Information was used to redesign the algorithm for the CR and educate the healthcare team to respond appropriately to the CR. The team focused on re-design and implementation of a more meaningful and reliable CR algorithm which would translate into decreased numbers of nuisance CRs, reminder fatigue (in nurses and physicians), and increased compliance to sepsis screening (early recognition and bundle adherence).

Interdisciplinary meetings/education

According to the National Association Clinical Nurse Specialists alarm safety is the number one technology hazard in health care. Excessive alarms in clinical environments lead to alarm fatigue: staff may ignore or disable a clinically important alarm (15). The team focus identified actions and planned to manage CRs effectively and safely, taking into consideration unit culture, infrastructure, nursing practice and technology. Following Cognitive and Organizational Science Principles to decrease reminder fatigue, team members examined the core principles of CRs including design and implementation (10). Using the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control) model, the project team conducted a gap analysis which sought to define appropriateness of CRs using reminder data from information systems report.

Working closely with the information technology specialist, analysis of the data was used to prioritize areas for improvement, to identify goals and determine how the changes will affect the algorithm and healthcare team workflow. The team strategies for the CR algorithm were to keep simple action items with multiple response options offered, while aggressively minimizing false alarms. Specific tasks included, detailing which alarms to change and the process to implement the change, including nurse related educational needs for pilot (staff education/competencies) and dates/times to monitor data. Strategies for CR management took into consideration algorithm defaults/escalation (dependent on user action), customization, evidence-based use of monitoring, clarification of user accountability, and policy development. An overarching goal was to ensure the algorithm fit into clinician workflow. The team ensured the CRs addressed quality goals both nationally and internally and implementation of the redesigned algorithm included support for the system; adaptability to clinician’s use and resources to make responding to reminders meaningful.

The new build (CR algorithm) was placed into a training environment and tested by the interdisciplinary project team for functionality allowing for revision as needed prior to developing education for the healthcare team. This process empowered the CNS and educator to deliver flawless training with confidence the end-user education would prepare the healthcare team for go-live and continued day-to-day usability. The last thing new users want to hear in training are excuses for a training environment or algorithm that is not working correctly. The new users practiced in the training environment and became comfortable and competent with use and response to the new CR tool. A user tip sheet was developed and shared with users as a quick go to reminder for appropriate use of the CR.

Prior to “go-live” of the new algorithm, the CNS attended nursing practice meetings attended by representatives from each nursing unit as well as nurse managers and clinical coordinators. This communication was also provided in physicians, residents, and physician extenders meetings. This intervention aided in reinforcement of process and allowed for voicing of questions or concerns by the front-line staff.

Lastly, a brief face-to-face presentation reinforced appropriate use of the sepsis CR. Emphasis was placed on incorporating nursing assessment and patient data and importance of notification of the provider in a timely manner of findings. The CNS and educator’s personal and individualized education addressed any last-minute concerns and issues with the CR with the frontline staff. A case study was shared to demonstrate collaboration within the healthcare team to satisfy sepsis/septic shock 3- & 6-hour bundle criteria. With the best interest of our patients in mind the education stressed appropriate and timely use of this CR as a means to: (I) assist with early identification and treatment sepsis/septic shock; (II) decrease mortality; and (III) decrease reminder fatigue and nuisance alarms.

Results

Data analysis

Survey data collected via an online survey cloud-based software was exported to excel software. Pivot tables served as a summarization tool to condense and trend nursing survey data. Categorical variables are expressed as counts with percentages in tables. CMS sepsis compliance rates (required to report to CMS) and hospital benchmark information reports were used as our outcome variable and were obtained via the hospital data abstraction system. Data abstractor workflow follows a detailed specifications manual provided by CMS entailing a procedure for sampling patients’ medical records.

CR algorithm revision

With NA documentation of vital signs, if a patient meets systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the NA receives a CR. Prior to the algorithm redesign; the NA could ignore/cancel the CR without action potentially contributing to failure to rescue. The redesign requires the NA to notify the registered nurse (RN) immediately (verses ignoring the CR) and then to enter the RN name to be able to “accept” and close window.

After being notified of the patient meeting SIRS criteria and upon opening the patient’s EHR, a CR appears for the RN. The new algorithm requires thorough review of the sepsis advisory, including incorporation of recent patient data and considerations from the most recent nursing assessment. To assist with this, the RN is prompted to open the Sepsis Navigator (a component of the new CR algorithm) directly from the CR by clicking on the hyperlink labeled, “CLICK HERE BEFORE SELECTING ACKNOWLEDGE REASON”. From the navigator, the RN confirms/or rules out suspicion of sepsis by answering a series of prompts. If sepsis is suspected, the nurse is prompted with requirements for reporting to the physician and for patient monitoring:

- Sepsis patients admitted to the med/surg floor:

- VS q 15 min ×4 is crucial to ensure the patient is not progressing to septic shock;

- Call the provider if the systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 or mean arterial pressure (MAP) <70 or

- Call the rapid response for the 2 consecutive SBP <90 or MAP <70.

- If patient progresses to septic shock and receiving the septic shock bolus:

- VS q 15 min ×4 crucial to assess for persistent hypotension;

- Call the rapid response for the 2 consecutive SBP <90 or MAP <70;

- Critical Care or Department of Emergency Medicine call for vasopressor orders.

The education included the specific path the algorithm follows for each of the CR Acknowledge Reasons a provider or nurse may choose:

- Provider notified: CR locked out for 48 hours—applies to all users;

- Attempted to notify provider: CR will not be locked out—applies to current user;

- Severe sepsis screening negative: CR locked out for 8 hours—applies to all users;

- Not on treatment team: CR locked out for four hours—applies to current user.

As important as the choice of acknowledge action to frequency of CRs, the design also accounted for documentation for SIRS criteria being met again (new patient data, i.e., vital signs/labs) and prompts a new CR. However, if patient meets sepsis/septic shock criteria and the sepsis order sets are initiated, no further CRs will be triggered. Choosing the appropriate acknowledge reason decreases the frequency of nuisance CRs and ensures the treatment path is initiated in a timely manner for those with sepsis/septic shock.

The algorithm redesign includes the Sepsis Navigator which follows workflow for sepsis in the EHR and includes:

- Comprehensive report: information to provide comprehensive care for all aspects of the patient’s health and well-being;

- Sepsis screening: criteria to identify early sepsis detection;

- Sepsis treatment: documentation for patient’s sepsis treatment;

- Provider notification: documentation for provider notification;

- Sepsis timer: time sepsis is identified;

- Sepsis report: information to assist with delivering care for the patient’s sepsis/septic shock diagnosis;

- SEP-1 documentation: information to assist with meeting the 3-hour bundle;

- Sepsis note: note type to be completed by the provider between 3 and 6 hours after severe sepsis/septic shock has been identified.

Sepsis bundle adherence

The institution’s inpatient hospital quality measures dashboard: sepsis: early management bundle, severe sepsis/septic shock—sampled for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Pre-project adherence (July 2017) =3%, post-project adherence (December 2017) =48% positive trending to near institutional goal with a 45% improvement with adherence to the sepsis bundle (institutional target ≥50%).

Inpatient optimal care (sepsis screening compliance)

The Balanced Scorecard—hospital core measure: inpatient optimal care score: sepsis (SEP-1) demonstrated a 94.85% increase in YTD 18 Actual 41.7% compared to YTD 17 Actual 21.4% (Data source—Quantros).

Sepsis mortality

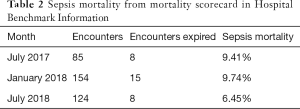

Hospital Benchmark Information mortality scorecard: July 2017 (9.41%), January 2018 (9.74%), & July 2018 (6.45%) (Table 2).

Full table

CRs for sepsis

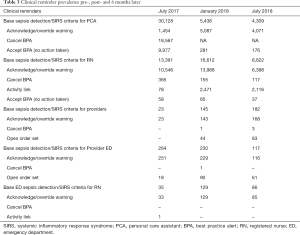

CR prevalence pre- and post-intervention and 6 months later are reported in Table 3.

Full table

Base sepsis detection/SIRS criteria for PCA (NA): July 2017—30,128 (pre-intervention) compared to January 2018—5,438 (post-intervention) and July 2018—4,309 (6 months later).

Base sepsis detection/SIRS criteria for RN: July 2017—13,391 (pre-intervention) compared to January 2018—16,612 (post-intervention) and July 2018—8,622 (6 months later).

Base sepsis detection/SIRS criteria for Providers: July 2017—23 (pre-intervention) compared to January 2018—145 (post-intervention) and July 2018—182 (6 months later).

Nursing survey

Nursing action (documentation) focused survey items

The majority of nurses surveyed reported their typical or usual documentation practice as being documented after they complete all of their shift patient assessments (41.95%). The nurses reported they typically collect and record patient vital signs themselves (64.39%). Patient vital signs were reported to be documented concurrently by the majority of nurses (48.78%). Only 25.37% of nurse stated vital signs were recorded on paper and documented at a later time in the EHR. The nurses believed there to be sepsis protocols in place throughout the institution (89.76%) however, 37.56% of nurses reported the adherence to the protocols was followed only some of the time or seldom (collectively) (see Table 4).

Full table

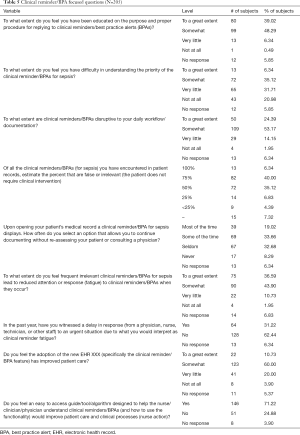

CR focused survey items

To what extent nurses feel they have been educated on the purpose and proper procedure to replying to CRs had the majority of responses being “somewhat” (48.29%). Nurses also responded most frequently, they felt they had “somewhat” difficulty understanding the priority of the CR (35.12%). CR disrupt daily workflow/documentation was reported to the extent “somewhat” (53.17%). Forty percent of nurses estimate the percent of CRs that are false or irrelevant (the patient does not require clinical intervention) is 75%. The majority of nurses (66.34%) report they seldom or some of the time select an option that allows you to continue documenting without re-assessing your patient or consulting a physician. Nurses feel to a somewhat extent frequent irrelevant CRs leads to reduced attention or response fatigue to CRs (43.90%). The majority of nurses did not feel there were delays in response to an urgent situation or harm to a patient due to CR fatigue. Nurses overall feel the CR feature of the new EHR, has “somewhat” improved patient care (60.00%) and feel an easily accessible guide to understand CRs and their functionality would improve patient care (71.22%) (see Table 5).

Full table

Discussion

Key results

The project aligned with the hospital strategic goals and results for sepsis screening are tracked on the organizational dashboard. The redesigned algorithm for sepsis CR supports regulations pertaining to the appropriate scope of practice for unlicensed assistive personnel. CRs triggered by vital sign documentation by NAs directs report to the RN as the only option for the NA. In addition, documentation practices (timing of assessment and vital sign documentation) were identified via the nursing survey and will be examined for any effect on triggering CRs and included in ongoing sepsis education. Nursing survey response of a belief there is lacking adherence to established sepsis protocols is concerning. Ongoing efforts directed in surveillance and support of nursing action in response to CRs for sepsis will be investigated.

Limitations/generalizability

There are several limitations to this study: first, it included a single academic center, and we do not know how it will perform in other settings, thus limiting generalizability. Larger-scale multicenter quality improvement collaboratives may help to address this concern

Although the project was supported by nurse and physician champions, sustainability is of concern with lack of a designated clinical sepsis coordinator for timely intervention and surveillance of bundle compliance to aid the bedside clinicians.

Interpretation

We hypothesized the revision of the CR for sepsis would decrease the frequency of nuisance CRs and alarm fatigue. We realize from survey results delayed documentation practices of nurses on general care floors may affect the triggering of the CR. In the ICU setting although the vital signs are often auto-recorded, the vital signs are not retained as part of the permanent record until “confirmed/reviewed/accepted” by the nurses. As important as education and response to the redesigned CR algorithm is appropriate documentation practices to not delay the CR from firing. The specific aims of our project as a result of our team efforts reduced the number of CRs for sepsis in the inpatient adult population (>18 years) through CR customization. We also feel the improvement in the percentage of patient’s being screened will result in improved patient outcomes. Sepsis mortality has trended positively since the algorithm roll-out. We continue to assess and analyze data to decrease CR fatigue in nurses and determine if nurses’ action to CRs for sepsis is appropriate and if it affect patient outcome (failure to rescue or delay in implementation of the sepsis bundle). This will be an ongoing effort.

New leadership both at an organizational level and at the institution level has challenged the quality department. Nurse turnover is at an all-time high limiting experienced nurses as mentors at the bedside. The next steps for the project team include continued auditing and integration of new evidence at the bedside through continued education and update of CRs.

At this time the team is working on development of an early prediction of sepsis analytics model. Access to this build was completed mid-summer [2018]. The information technology specialist built the tool to run in the background with CR documentation. The information will be reviewed to determine pertinent data and determine how we can work the information into our workflow to continue our efforts to improve adherence to screening, decrease alarm fatigue, and improve outcomes for patients with sepsis/septic shock.

We have demonstrated using human factors and cognitive science principles in the CR algorithm design is an approach to avoid reminder fatigue and improve adherence to screening policy. At times the highly variable audit results may be explained by the impact of dynamic leadership and staff turnover. It is important to proactively forecast potential issues and have succession plans in place so these issues do not derail efforts resulting in costly consequences. Continuing to incorporate these principles into future CR designs and updated versions of EHR coupled with ongoing staff education, our goals of improved quality and outcomes may be better realized.

Recognizing every unit has its own unique mix of resources, culture, patient population, documentation norms, and multiple other factors, specific patient care and safety challenges must be identified and prioritized for quality improvement efforts. The CNS was successful in collaborating with the interdisciplinary team to support the redesign of the sepsis CR. In addition, the CNS developed documentation, policies, and procedures to support this new technology/process. Success was evidenced by support of and growth of the program over time, decrease in CRs and an increase in screening compliance.

Supplementary file 1

Nursing survey—sepsis clinical reminders and nurse action

What is your typical (usual) nursing documentation practice?

- Concurrently (at the same time) as you assess your patient

- Immediately after you finish each patient assessment

- After you complete all of your shift patient assessments

- At the end of your shift

Which staff member typically collects and records patient vital signs on your unit?

- Myself

- Another registered nurse

- A licensed practical nurse (LPN)

- A nursing assistant/clinical assistant

Are patient vital signs documented:

- Concurrently (at the same time) as vital signs are being measured

- Immediately after each patient’s vital signs are measured

- After all of the patient vital signs are obtained or that time period

- At the end of the shift

Are patient vital signs typically recorded on paper and documented at a later time in the electronic medical record?

- Yes

- No

Please select what you believe is current practice at XXXXXX.

- Sepsis protocols in place for patients who present to the emergency department

- Sepsis protocols in place for inpatient

non-ICU patients - Sepsis protocols in place for ICU patients

- Sepsis protocols in place throughout the institution

- No sepsis protocols in place

Based on answer to previous question, to what degree do you perceive adherence (the extent to which the persons’ behavior corresponds with agreed recommendations) to establish protocols for sepsis?

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- Seldom

- Never

- No sepsis protocols in place

To what extent do you feel you have been educated on the purpose and proper procedure for replying to clinical reminders/best practice alerts (BPAs)?

- To a great extent

- Somewhat

- Very little

- Not at All

To what extent do you feel you have difficulty in understanding the priority of the clinical reminder/BPAs for sepsis?

- To a great extent

- Somewhat

- Very little

- Not at all

To what extent are clinical reminders/BPAs disruptive to your daily workflow/documentation?

- To a great extent

- Somewhat

- Very little

- Not at all

Of all the clinical reminders/BPAs (for sepsis) you have encountered in patient records, estimate the percent that are false or irrelevant (the patient does not require clinical intervention).

- 100%

- 75%

- 50%

- 25%

- <25%

Upon opening your patient’s medical record a clinical reminder/BPA for sepsis displays. How often do you select an option that allows you to continue documenting without re-assessing your patient or consulting a physician?

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- Seldom

- Never

To what extent do you feel frequent irrelevant clinical reminders/BPAs for sepsis lead to reduced attention or response (fatigue) to clinical reminders/BPAs when they occur?

- To a great extent

- Somewhat

- Very little

- Not at all

In the past year, have you witnessed a delay in response (from a physician, nurse, technician, or other staff) to an urgent situation due to what you would interpret as clinical reminder fatigue?

- Yes

- No

Comment (optional): ________________________________________________________________

In the past year, have you witnessed patient harm as a result of clinical reminder fatigue?

- Yes

- No

Comment (optional): __________________________________________________________________

Do you feel the adoption of the new EHR, XXX (specifically the clinical reminder/BPA feature) has improved patient care?

- To a great extent

- Somewhat

- Very little

- Not at all

Do you feel an easy to access guide/tool/algorithm designed to help the nurse/clinician/physician understand clinical reminders/BPAs (and how to use the functionality) would improve patient care and clinical processes (nurse action)?

- Yes

- No

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the important contributions of Courtney Boast, BS (Application Systems Analyst, Clinical Documentation, Decision Support, Management Information Systems) and the entire interdisciplinary team for their tireless efforts to improve patient outcomes and support the efforts of the bedside clinicians.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The project underwent an internal review process and received final administrative approval by The Office of Research Administration at the project site. The study was deemed exempt, as part of a hospital quality improvement initiative. All potentially sensitive audit data was accessible only to authorized personnel and stored using institutionally recommended security protocols.

References

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med 2015;43:3-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cebul RD. Using electronic medical records to measure and improve performance. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2008;119:65-75; discussion 75-6. [PubMed]

- Moja L, Liberati EG, Galuppo L, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of computerized clinical decision support systems in specialty hospitals: protocol for a qualitative cross-sectional study. Implement Sci 2014;9:105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2001.

- Capsule Tech. Harnessing the power of medical device data: introducing the medical device information system. 2015. Available online: http://webinfo.capsuletech.com/harnessing-power-medical-device-data-whitepaper

- Morgan R, Lloyd-Williams F, Wright MM, et al. An early warning scoring system for detecting developing critical illness. Clin Intensive Care 1997;8:100.

- Militello L, Patterson ES, Tripp-Reimer T, et al. Clinical Reminders: Why Don't they use them? Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2004;48:1651-5. [Crossref]

- Green LA, Nease D Jr, Klinkman MS. Clinical reminders designed and implemented using cognitive and organizational science principles decrease reminder fatigue. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:351-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mushta J, L, Rush K, Andersen E. Failure to rescue as a nurse-sensitive indicator. Nurs Forum 2018;53:84-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission: safe use of health information technology. Sentinel Event Alert #54, March 31, 2015 (accessed October 1, 2018). Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_54.pdf

- American Hospital Directory. Available online: https://www.ahd.com/

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Chapter 3: Getting involved in the research process. In: Effective Health Care Program Stakeholder Guide. Rockville, MD: AHRQ 2014:11-26. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/stakeholderguide/chapter3.html

- National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. Alarm fatigue. 2016. Available online: https://nacns.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/AF-GetStarted.pdf

Cite this article as: Drahnak DM. An observational study of the effects of a clinical nurse specialist quality improvement project for clinical reminders for sepsis on patient outcomes and nurse actions. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2018;2:99.