Massive retrosternal goitre causing stridor and respiratory distress—a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

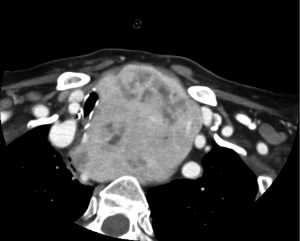

• Stridor and respiratory distress secondary to goitre is rare. These slow growing lesions don’t usually present acutely like this. The key findings here are the radiology images. A computed tomography neck which portrays an extremely impressive, easily interpreted, textbook images of tracheal deviation and stenosis and a chest X-ray which shows textbook soft tissue mediastinal swelling with tracheal deviation to the right.

What is known and what is new?

• Surgical resection is the standard of care in goitre with compressive symptoms. Literature on airway management in cases like this all concern elective intubations in tertiary hospitals with specialist surgical intervention immediately available. Intubation in an unsupported rural setting may prove catastrophic. However, transfer with unsupported airway may be equally problematic. This case highlights issues encountered in best management of such cases in a rural setting.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This case highlights a lack of data involving management of impending mechanical airway obstruction in non-specialist centres. More data is needed on best practice in such cases.

Introduction

Airway compromise represents an immediate concern to anyone involved in emergency medicine and critical care with stridor being recognised as a possible impending airway emergency. Stridor is caused by airway obstruction, classically inspiratory stridor representing obstruction above or at the level of the vocal cords and expiratory or mixed stridor representing obstruction below the cords. Stridor in adult patients presenting from the community is most commonly due to neurological causes, local vocal cord lesions or psychogenic causes (1). It can also be caused by anaphylaxis, foreign body inhalation, tumours or any cause of tissue oedema. Benign multinodular goitre is a common condition but rarely causes airway compromise, with an incidence of airway obstruction in patients with goitre of just 0.6% (2). Clinical management of such cases, remains a challenge. Here we describe the difficulties encountered and management considerations in the case of a 90-year-old lady presenting to the emergency department (ED) in acute respiratory distress from airway obstruction due to a massive retrosternal goitre. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-54/rc).

Case presentation

An independent 90-year-old woman presented to the ED with shortness of breath in the early hours of the morning. She reported worsening symptoms over the previous 3 days. She had been living at home alone and had recently finished a course of antibiotics for a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI). Background medical history included a right sided thyroidectomy 10 years previously for right sided non-toxic goitre, varices, osteoporosis and cataract surgery. She had been discharged from the care of her thyroid surgeon. The patient was a non-smoker. She had an inpatient admission with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 1 year previously, which was successfully managed at ward level.

On examination respiratory distress was immediately evident with the patient adopting the tripod position at the end of the bed. Stridor was readily observed in both the inspiratory and expiratory phase of breathing. Accessory muscles were in use and tracheal tug was evident. Chest auscultation revealed good air entry bilaterally. Examination also revealed positive Pemberton’s sign. No masses were apparent or palpable in her neck. On examination of her airway, she had a Mallampati score of 2, a normal thyromental distance, with adequate mouth opening. She was edentulous. The patient was tachypnoeic but able to speak short sentences. Vital signs included a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute, heart rate of 90 bpm, blood pressure of 175/100 mmHg. Her temperature was normal. SpO2 was 93% on 4 litres of oxygen through nasal prongs. Airway manoeuvres such as jaw thrust, and chin lift did not improve her condition. She was prescribed intravenous antibiotic (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1.2 g), intravenous dexamethasone 8 mg, two doses of nebulised epinephrine 5 mg each and two doses of nebulised salbutamol/ipratropium (5 mg/0.5 mg) which had little to no beneficial effect on her symptoms. Non-invasive ventilation was commenced but the patient did not tolerate this treatment as it exacerbated her anxiety and breathlessness. A chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) neck were both booked.

Chest X-ray showed tracheal deviation to the right and a mediastinal mass (Figure 1). A CT scan of her neck showed tracheal stenosis with minimum diameter of 0.6 cm at level of thoracic inlet, caused by massive retrosternal goitre (Figures 2,3). The goitre measured 77 mm × 89 mm × 123 mm; arterial blood gas (ABG) on 4 L nasal prongs; revealed type 1 respiratory failure with PaO2 65 mmHg and PCO2 of 33 mmHg; PH was 7.47. Other blood tests revealed her haemoglobin was 12 g/dL. White cells were 6.8×109/L and C-reactive protein was 2.7 mg/L. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm with no significant abnormalities.

While the patient was hemodynamically stable, and did not show signs of further deterioration, medical treatment in the ED provided little to no clinical improvement. Given her impressive CT findings and mechanical airway obstruction, surgical opinion was sought.

The patient made it clear that she did not want major surgery. Her family fully respected her decision. Upon consultation with Ear, Nose, Throat (ENT) doctors in a nearby hospital, the option of minimally invasive palliative procedures was considered. The decision was made to transfer her urgently to a head and neck centre with full time ENT cover for consideration of palliative tracheal stenting or suture lateralization. She spent less than three hours in our hospital between arrival and treatment, and was transferred in an ambulance, on 60% FiO2 by venturi mask. The transfer took 25 minutes. An anaesthesiology registrar and an emergency nurse accompanied her on transfer. The patient was transferred uneventfully, and monitored in a head and neck centre while treatment options were discussed. While discussing treatment options with the surgeons and her family, the patient made it clear that she did not want to be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) department and did not wish to be intubated in the event of deterioration, nor did she want to have any surgery. The option of suture lateralisation and possible tracheostomy was raised, but ultimately the patient refused this intervention. The decision was made to prioritise her comfort as per her wishes, and she died 2 weeks later in a palliative care setting. The patient kindly consented to publication of her case prior to her death.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Here we present the case of a common treatable illness causing an acute airway emergency, and ultimately the death of a patient. Acute airway obstruction from multinodular goitre is rare, accounting for only 0.6% of all goitres (2). These lesions are slow growing, and tolerance to large goitres is well described, with some patients having no symptoms despite tracheal compression of up to 70% (3). In this context the relevance of the patient’s recent LRTI may be drawn into question, with airway oedema, secretions, coughing fits and airway irritation a probable driving factor for her acute decompensation.

Surgical intervention is the treatment of choice for goitres with compression symptoms (4,5). One study analysed 1,115 patients presenting for thyroid surgery and identified 7 of these patients as presenting with airway emergencies. Prompt airway protection followed by early total thyroidectomy was the recommended course of action in such patients (2). This study was done in a dedicated head and neck centre. Intubation was out of the question in this case due to patient refusal, but ultimately the question of best management in peripheral centres is unclear. Data on best emergency management outside of head and neck centres are scarce. Is transferring the patient as soon as possible for consideration of safe intubation in a specialist centre the right option, or is the best course to try to secure an advanced airway in a sub optimal setting, with minimal surgical support?

This case is a good example of why communication, and listening to patient concerns is important. Here, the patient and her family expressed concerns over intubation, and major surgical intervention. Undoubtedly, these concerns have to be respected. However, this does not preclude her from having expert opinion. We were not equipped to discuss with the patient and her family, how invasive each palliative ENT option would be. With this in mind transferring to ENT centre for consideration of various palliative procedures was, in the authors opinion the right decision. With regards to her pathology, this case highlights numerous challenges regarding best management of mechanical airway obstruction in rural centres. This patient did not wish for definitive management, the next patient may. In this instance, there was an inexperience of staff dealing with such cases and no access to specific ENT instruments such as rigid bronchoscopy. The data shows patients with large goitre may not prove difficult to intubate in the context of being in a specialised centre and in an elective setting. Transfer to an ENT centre has to be considered if the patient is stable enough. It is the authors opinion that a judgement call has to be made on a case-to-case basis. In this case transfer took only 25 minutes. There was a risk that the patient may deteriorate in this time and her airway may obstruct. Many hospitals worldwide are further from ENT centres than 25 minutes. Should this shape our management? Of course, if the patient crashed, there would be no choice but to attempt intubation. Intubating electively before transfer may also result in airway occlusion with administration of neuromuscular blockade, or instrumentation of an already oedematous airway. This case demonstrates that it is possible to have a scenario where both options are sub optimal. It is the authors opinion that personalised medicine has to be utilised and a judgement call has to be made based on what is considered safest for the patient in each individual case.

Among anaesthesiologists, retrosternal goitre causes concern with a wide held belief that difficult intubation could be common in these patients (6,7). This concern is likely based on anecdotal evidence or case reports, with little support from wider studies done on patients with retrosternal goitres undergoing thyroidectomy (8,9). Bouaggad et al. analysed 320 patients undergoing thyroidectomy and found that only 5.3% had difficult endotracheal intubation (8). A retrospective analysis done by Pan on 22 patients with giant retrosternal goitre found that all were intubated uneventfully by either direct laryngoscopy or video laryngoscopy (9). Both of these studies were done in Tertiary centres, on patients undergoing thyroid surgery where difficult airways would be more anticipated, and more frequently encountered, than in an ED. It is the authors opinion that more data is needed on intubation outside of theses elective cases, in emergency settings and outside of tertiary centres.

Difficult Airway Society (DAS) guidelines for difficult intubation provide a clear approach plan A–D (10). In the event of a “cannot intubate cannot oxygenate” scenario, front of neck access via cricothyroidotomy (plan D) would undoubtedly prove incredibly challenging. Further considerations would involve positioning the patient safely, and the use of a gas induction or awake fibreoptic intubation.

In this case, the patient made clear her wishes that she did not want to be intubated and did not want to have surgery. She clearly had capacity and her wishes were respected. It is important however that we understand and familiarise ourselves as critical care and emergency doctors, what best practice is in such cases.

Conclusions

Acute airway compromise from retrosternal goitre is rare. Current literature describes best management as early airway protection followed by prompt thyroidectomy. This was not possible in our case as the patient did not consent to intubation, or major surgery. In this case, patient refusal for escalation of care was an absolute contraindication to intubation or surgical management. However, this did not preclude her from expert opinion. Evidence on airway management in patients with large retrosternal goitres suggest that intubation should not prove difficult. This data is mainly confined to Tertiary hospitals with senior anaesthesiologists and ENT surgeons and mostly from the elective setting. More data are needed on best management of these patients in the ED in rural centres where expert opinion may not be available.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-54/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-54/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jeccm-24-54/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zochios V, Protopapas AD, Valchanov K. Stridor in adult patients presenting from the community: An alarming clinical sign. J Intensive Care Soc 2015;16:272-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abraham D, Singh N, Lang B, et al. Benign nodular goitre presenting as acute airway obstruction. ANZ J Surg 2007;77:364-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaha AR, Burnett C, Alfonso A, et al. Goiters and airway problems. Am J Surg 1989;158:378-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurley DL, Gharib H. Evaluation and management of multinodular goiter. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1996;29:527-40. [PubMed]

- Ríos A, Rodríguez JM, Canteras M, et al. Surgical management of multinodular goiter with compression symptoms. Arch Surg 2005;140:49-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bennett AM, Hashmi SM, Premachandra DJ, et al. The myth of tracheomalacia and difficult intubation in cases of retrosternal goitre. J Laryngol Otol 2004;118:778-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilfillan N, Ball CM, Myles PS, et al. A cohort and database study of airway management in patients undergoing thyroidectomy for retrosternal goitre. Anaesth Intensive Care 2014;42:700-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouaggad A, Nejmi SE, Bouderka MA, et al. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation in thyroid surgery. Anesth Analg 2004;99:603-6. table of contents. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan Y, Chen C, Yu L, et al. Airway Management of Retrosternal Goiters in 22 Cases in a Tertiary Referral Center. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020;16:1267-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Difficult Airway Society. DAS Guidelines for Management of Unanticipated Difficult Intubation in Adults 2015 | Difficult Airway Society [Internet]. das.uk.com. 2015. Available online: https://das.uk.com/guidelines/das_intubation_guidelines

Cite this article as: O’Connor E, Looney M, Lennon E. Massive retrosternal goitre causing stridor and respiratory distress—a case report. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2025;9:6.